Videoconferencing has been around in one form or another for quite a while, but it took the pandemic to thrust into prominence with just about everyone. In a way, it has been the delivery of something long-promised by phone companies, futurists, and science fiction writers: the picture phone. But very few people imagined how the picture phone would actually manifest itself. We thought it might be interesting to look at some of the historical predictions and attempts to bring this technology to the mass market.

The reality is, we don’t have true picture phones. We have computers with sufficient bandwidth to carry live video and audio. Your FaceTime call is going over the data network. Contrast that with, say, sending a fax which really is a document literally over the phone lines.

So how did people imagine picture phones? And when did they become available? The answers might surprise you. We aren’t sure how far back people imagined such a device, but we know that one was built as early as 1930.

So how did people imagine picture phones? And when did they become available? The answers might surprise you. We aren’t sure how far back people imagined such a device, but we know that one was built as early as 1930.

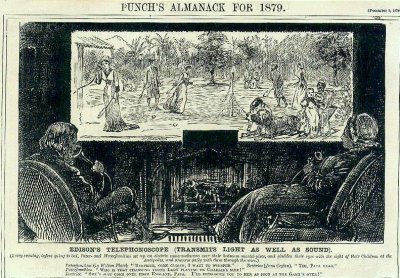

Even as early as the 1870s, science fiction mentioned telephonoscopes, an intention a cartoonist attributed to a future version of Thomas Edison. Alexander Graham Bell did think such a thing was possible and even wrote of using selenium as a way to sense light to convert it into electricity. He knew, though, that the sensor would have to be very tiny. This was years before electromechanical TV started to appear in the early part of the 20th century.

A Brief Survey of Picture Phones

You can argue what exactly constitutes a picture phone. AT&T offered a picture phone commercially in 1992 — we’ll talk about it soon — that showed black and white images at 10 frames per second. While that’s crude by today’s standards, most people would agree it was video. But some old attempts used something akin to what ham radio operators call slow scan TV. A camera would grab a black and white image and send it fax-like via audio tones. That means you got an 6- or 8-second delay and you could see the picture. Most people wouldn’t consider that video, but it is a slippery slope where you draw the line.

We remember Radio Shack briefly advertising these phones, although we can’t find any evidence of it now. But we think they were Mitsubishi Luma phones. Regardless, these kinds of phones were mostly novelties and didn’t sell well in the consumer space.

Ancient History

It is no secret that the phone company itself had the biggest interest in Picturephones (a trademark) and, in fact, everyone assumed that by 2001, every payphone would have a camera and a screen. Not many people thought the payphone itself would be an endangered species. Even the 1927 classic Metropolis had a video phone call in it.

The phone company started working on video calling when it sent a speech by Herbert Hoover — then the Secretary of Commerce — from Washington to New York in 1927. The video was only one way and with a limited frame rate. The New York Times noted that Hoover’s face was not clearly distinguishable.

The equipment used probably looked like the 1927 prototype seen here. The scanning for the image was done with a mechanical disk, which is limiting.

The equipment used probably looked like the 1927 prototype seen here. The scanning for the image was done with a mechanical disk, which is limiting.

Getting that much data across phone lines would be a challenge before there was any way to compress the signal. In fact, the image traveled over multiple phone lines. With a mechanical system, the motors on the sending and receiving disk also needed to be synchronized, presenting another technical challenge. The phone company kept working on this system — dubbed Ikonophone — for several years with a team of around 200 people. Work slowed during World War II, but by the 1950s, the company would resume work on the system now known as Picturephone.

Meanwhile, in other parts of the world, Germans had public video phone service as early as 1936 between the post offices in Berlin and Leipzig. A dedicated cable 100 miles long connected the two phones that combined a flying-spot scanner and a cathode ray tube. The video was respectable, at 25 frames per second and 150 lines of resolution. The system eventually increased to 180 lines of resolution and other routes including Hamburg, Munich, and Nuremberg. Each city had two booths and a call cost about 1/15th of the average worker’s weekly wage. The French also had a similar system. These post office video phones, like the United States version, halted during the War.

Picturephone

By the mid-1950s, prototype picture phones using signal compression could transmit an image every two seconds over regular phone lines. The phone contained a storage tube or magnetic drum. By 1964, the Picturephone Mod I which had a better frame rate was seen at the New York World’s Fair and Disneyland. By 1964, there were several Picturephone booths, but they were not very popular, mainly because of the cost which could be as high as $27 for three minutes — over $250 today. By 1968, the phonebooths were gone.

The Mod II, however, found use for videoconferencing in 1970. The cost was high. The phone cost $150 along with a service fee of about $160 per month for the first phone and $50 for each additional phone. For that price, you got a whole 30 minutes of calls, after which you would pay a quarter a minute. Eventually, the price came down, but it was a lot of money in the early 1970s.

For that price, you got about 250 lines of resolution at 30 frames per second. It looks like you also needed a speakerphone for the audio and — by way of an additional box — signaling. There were two separate phone lines for the video. Early models were not color.

Final Analysis

Unfortunately for AT&T, the video phones they had developed over decades were a commercial failure. The official program alone was over 15 years and cost around $500 million. The phone company had predicted 100,000 phones in service by 1975. The real number was in the hundreds.

They tried again in the early 1990s with the VideoPhone 2500 marketed at consumers. At $1,500 a pop and anywhere from 10 frames per second to 1/3 of a frame per second, they didn’t sell very well. Surprisingly, they apparently sold about 30,000 units, but that was hardly enough to recoup their investment.

Other countries tried similar systems with similar results. France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom all had some form of video phone and all suffered from the same problems — low bandwidth over phone lines is simply not conducive to live video.

The answer would be digital networks and techniques, even though that wasn’t always obvious. For example, ARCNET — an early competitor to Ethernet — could — in some configurations — reserve bandwidth for analog video signals.

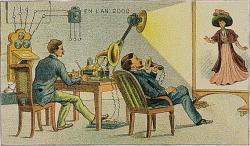

You can compress video with digital techniques, and network bandwidth has been on an upward slope. So as compression gets better, bandwidth goes up, and today it isn’t unusual to video conference with a large number of participants at once. While it doesn’t look much like Villemard’s 1910 imagining of videoconferencing in the year 2000, it isn’t that far off, either.

If you have the urge to hack something related, you can create a mirror system that lets you read your screen and make eye contact at the same time. Or, be a real hacker and do your conferences in text mode. We’re just glad today’s version of the video phone doesn’t let you see us pacing in the control room waiting for a call like the one in Metropolis (see below) does. We still aren’t sure what the paper tape coming out of those phones is for.

Where Are Our Video Phones?

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments