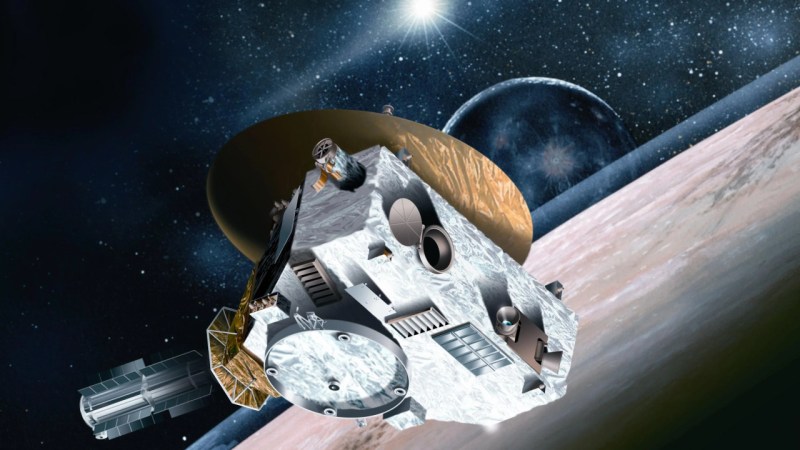

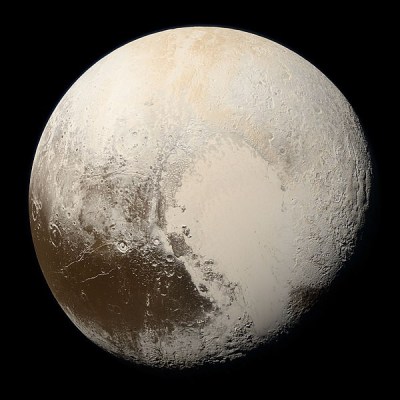

In 2015 NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft provided humanity with the first up-close views of Pluto, passing just 12,472 km (7,750 mi) from the surface. What had always been little more than a fuzzy blip at the edge of the solar system could finally be seen in stunning high resolution. Unfortunately, the deep space probe could only provide us with a relatively fleeting glimpse at the mysterious dwarf planet — the physics of such a distant interplanetary flight meant the energy required to slow down and enter orbit around Pluto was beyond the tiny spacecraft’s abilities.

The craft, often described as being roughly the size and shape of a grand piano, raced past Pluto and its moons at a relative velocity of approximately 49,600 km/h (30,800 mph) and headed out in the direction of Sagittarius. The incredible rate at which New Horizons traveled officially put it on track to be just the fifth spacecraft to leave the solar system, after the Pioneer and Voyager probes. Even so, its onboard systems were still in good health, and if given a sufficiently distant target, the $700 million craft was ready and able to collect more data.

Accordingly, almost exactly a year after it flew over Pluto, New Horizons officially received a mission extension from NASA. As it blasted through deep space, the craft would seek out and study as many objects as it could in the region of space known as the Kuiper belt. Given that there are no current plans to send other spacecraft through this distant area of the outer solar system, New Horizons was uniquely positioned to make what could be once-in-a-lifetime observations.

Or at least, that was the plan. Recently, notes from a May 4th meeting of the Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) were released that revealed NASA’s plans to redirect New Horizons from its work in the Kuiper belt to focus on heliospheric science in 2025. Those in attendance said the meeting became “heated” as New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern questioned the logic of potentially changing the craft’s mission this late in the game.

Needle in a Haystack

To be fair, NASA’s logic for reassigning New Horizons does make sense. The space agency believes that the chances of the probe running into objects worth studying go down as the spacecraft gets farther and farther away. After all, space is mindbogglingly large. Despite how an artist’s representation of areas like the asteroid belt might appear, the distance between individual objects is immense. Further complicating matters it the fact that many of these Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) are relatively tiny, measuring just 30 to 55 km (19 to 34 mi) in diameter.

But even if there were plenty of fascinating objects in front of New Horizons, the craft itself is limited in the sort of course corrections it’s capable of. For the same reasons it couldn’t stop at Pluto, it can’t make very large changes to its trajectory, and even “small” changes can be very expensive from a propellant perspective. Accordingly, as of the last survey in November 2020, no notable KBOs were found along the probe’s current trajectory.

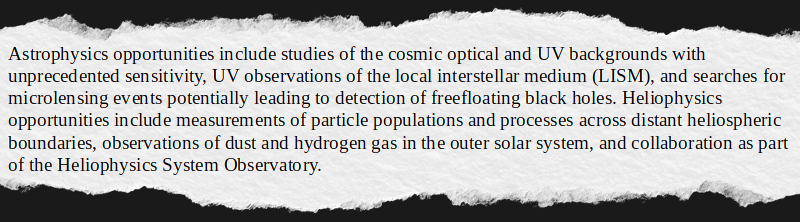

On the other hand, simply flying through this area of space exposes it to an environment we’ve had little chance to study. In NASA’s 2022 NASA Planetary Mission Senior Review, they pointed out several areas in which New Horizons could make important scientific contributions thanks to its extreme distance.

Current power and propellant usage estimates indicate that New Horizons should remain fully operational until at least the 2030s. By this time, it will likely have passed through the bulk of the Kuiper belt. NASA’s argument is that, while not technically designed for it, the probe’s remaining life would be better spent making valuable astrophysics and heliophysics observations than chasing down dwarf planets and other KBOs, which it may never find.

Kuiper Accomplishments

While it’s increasingly likely New Horizons won’t make any more close passes of Kuiper belt objects, the probe has certainly kept itself busy since its flyby of Pluto in 2015.

In January 2019, it made a close approach to 486958 Arrokoth — the farthest and most primitive solar system object to be directly observed by a spacecraft. Known as a contact binary, Arrokoth is the result of two objects gravitating so close to each other that they touch and become one. The peanut-shaped object was completely unknown until 2014, but thanks to the sensors aboard New Horizons, we have a surprisingly complete record of its geology.

While none of them have been as closely observed as Arrokoth, New Horizon has since imaged dozens of objects from its unique vantage point. Due to their small size, many of these objects would have been all but undetectable with existing telescopes.

On the other hand, some of the objects, such as the dwarf planet Haumea and Neptune’s largest moon Triton, were observed from an incredible distance. Images were even taken of nearby stars Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359, which, when combined with images taken from Earth, were able to demonstrate stellar parallax for the first time.

In short, while the future of New Horizons may remain uncertain, it has already far exceeded its original mission and will certainly be regarded as one of the most successful interplanetary probes ever launched. From its history-making study of Pluto to the closest observations we’ll likely ever get of distant solar system objects, the craft has certainly kept itself busy in the vast expanse of deep space. Regardless of what happens from 2025 on, the legacy of the New Horizons mission is beyond reproach.

New Horizons joins an elite club of human spacecraft operating far from home. We often wonder how Voyager is still talking after all this time. We’ve also peeked at some of the engineering behind Pioneer.

Change of Plans for New Horizons Sparks Debate

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments