Audio in cars has a long history. Car radios in the 1920s were bulky and expensive. In the 1930s, there was the Motorola radio. They were still expensive — a $540 car with a $130 radio — but much more compact and usable. There were also 8-tracks, cassettes, CDs, and lately digital audio on storage media or streamed over the phone network. There were also record players. For a brief period between 1955 and 1961, you could get a car with a record player. As you might expect, though, they weren’t just any record players. After all, the first thing to break on a car from that era was the mechanical clock. Record players would need to be rugged to work and continue to work in a moving vehicle. As you might also expect, it didn’t work out very well.

It all started with Peter Goldmark, the head of CBS Laboratories. He knew a lot about record players and had been behind the LP — microgroove records that played for 22 minutes on a side at 33.3 RPM instead of 5 minutes on a side at 78 RPM. He knew that a car record player needed to be smaller and shock-resistant. Of course, in those days, it would have tubes, but that could hardly be helped.

The problem turned into one of size. A standard 10- or 12-inch disk is too big to easily fit in the car. A 45 RPM record would be more manageable, but who wants to change the record every three or four minutes while driving?

A Plan

Goldmark slowed the record player down to 16.7 RPM. The records used a very tight pitch of 550 groovers per inch. This required a much thinner groove than conventional records, too. For records where high fidelity wasn’t an issue, a smaller center label allowed up to an hour to play on each side. For music, where the audio quality near the center wasn’t acceptable, they used a normal label and settled for 45 minutes of play time.

To help prevent skipping, the very tiny stylus was under unusually high pressure, and the records were made dense to resist wear from the heavy pressure. The 7-inch disks used as much plastic as a conventional 10-inch record. While a conventional stylus might be as small as 0.5 mils, the Highway Hi-Fi stylus was 0.25 mils! That’s just a bit more than 6 microns!

There was also a special design for the tonearm. It couldn’t move vertically, for example. A three-point suspension tried to minimize motion at the stylus, too. Since CBS developed the format, the only records you could get were from the CBS label.

On the Road

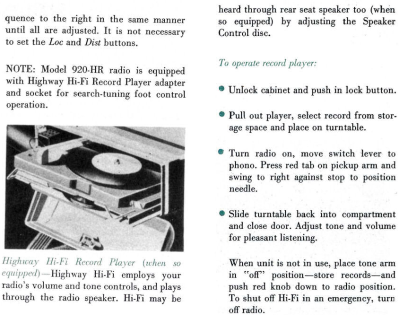

In 1955 Chrysler introduced “Highway Hi-Fi” for the 1956 model year. You could only buy the unit, which sat under the dash, as a factory option or have it installed by an authorized distributor. There was storage space for six of the new records. The October 1955 press release mentioned the unit was four inches high and less than a foot wide. The definition of hi-fi has changed a bit since the release also brags that the record player “reaches 10,000 cycles per second.”

But there were problems. First, you couldn’t use the records you already had, nor could you grab the new records and play them somewhere else. They only fit in your car’s player. If you got a different car brand or decided not to install a Highway Hi-Fi in the new one, your records were now worthless to you. Besides, there were only 42 different records available in the new format. You can see a very rare “new old stock” Highway Hi-Fi in the video from [Lou Costabile] below.

Like the mechanical clocks, too, the record players started to break down. A lot. By 1957, Chrysler was taking a beating on warranty service for the units and started quietly withdrawing them.

We are pretty sure the mechanical parts were responsible for many of the malfunctions, but there were other problems, too. The Highway Hi-Fi used an AC induction motor. Your car, of course, has DC power, so the unit incorporated a vibrator power supply. These are both noisy and highly prone to failure.

Not the End, Not Yet

In 1960, RCA tried again with a player that would work with standard 45s. They were even less reliable than the CBS units, and standard 45s were quickly worn out by the high-pressure stylus. By 1961, the thing was dead.

The RCA player incorporated a 14-disk changer and could store more disks than it could play. With extended-play 45s, you could get about 2.5 hours of music before you had to change disks. The tonearm was under the stack of records and played the bottom side of the disk. To change records, the tonearm cleared a path, and the record dropped underneath the arm. You can clearly see this in [George Borrelli’s] demonstration video, below.

Norelco/Philips also came out with a smaller record player that only held one 45. The Auto Mignon didn’t store records, and a single 45 would play for less than five minutes. From watching a video of the device below, it looks like a lot of it was suspension springs.

As an aside, after a court case in 1943, Philips was legally enjoined from using Philips on anything they sold in the United States. The courts decided it sounded too much like Philco, and that’s why in the United States, you saw these branded as Norelco while the rest of the world saw the Philips brand.

Despite limitations, the Auto Mignon was relatively cheap ($57.50) and installable into any vehicle. We aren’t exactly sure when they faded off the market, but it was just a matter of time, anyway. In 1962, Earl Muntz started selling 4-track tape players and music on “CARtridges,” but mostly in California and Florida. Then Bill Lear introduced the 8-track in the early 1960s. The rest, as the say, is history.

If you think audiobooks are a modern idea, the video below might change your mind. We didn’t find much information on these, but these disks are strange since they are fine-groove 16 RPM records, but it appears they were made for a custom player we’ve never heard of before. Note that the center hole looks more like a 45, while the Highway Hi-Fi had a small hole like an LP. Maybe someone who knows more about this mysterious system will enlighten us in the comments.

Timing is Everything

Controlling the music you hear in your car was the right idea, but these devices were just a little too early. Honestly, the fact that they seemed to work as well as they did was surprising. Ultimately, though, it would take advances in tape technology to make on-demand car audio practical. Tape gave way to optical, and now, all most people care about is integration with streaming from their cell phones. You have to wonder what will be next.

If record players are not familiar tech to you, we can help you out. If you are surprised that some people could pick their music in a 1959 automobile, would you believe a navigation system in the 1970s? Or the 1980s? Or even earlier?

Retro Gadgets: I Swear Officer, I was Listening to 45

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments