When the Space Race kicked off in earnest in the 1950s, in some ways it was hard to pin down where sci-fi began and reality ended. As the first artificial satellites began zipping around the Earth, this was soon followed by manned spaceflight, first in low Earth orbit, then to the Moon with manned spaceflights to Mars and Venus already in the planning. The first space stations were being launched following or alongside Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and countless other books and movies during the 1960s and 1970s such as Moonraker which portrayed people living (and fighting) out in space.

Perhaps ironically, considering the portrayal of space stations in Western media, virtually all of the space staions launched during the 20th century were Soviet, leaving Skylab as the sole US space station to this day. The Soviet Union established a near-permanent presence of cosmonauts in Earth orbit since the 1970s as part of the Salyut program. These Salyut space stations also served as cover for the military Almaz space stations that were intended to be used for reconnaissance as well as weapon platforms.

Although the US unquestionably won out on racing the USSR to the Moon, the latter nation’s achievements granted us invaluable knowledge on how to make space stations work, which benefits us all to this very day.

Sense And Nonsense Of Space

Why even put a habitat in orbit, whether it’s in low-Earth orbit (LEO), around the Moon or the massive space colonies in O’Neill cylinders, as popularized in sci-fi? Although less flashy than a daring trip to the Moon to perform experiments on its surface, there is a lot of practical use for having a constantly habitable space in microgravity. This is demonstrated by the International Space Station (ISS), which performs a range of experiments every single day, both inside and outside the station.

By removing gravity as a factor, its effect on everything from the way fluids behave during an experiment to how lifeforms grow can be examined and quantified. Space stations also form an excellent location to gather information on how to keep human beings alive with and without artificial gravity before we venture further into space and onto other planets. Another essential feature is the convenience of having a spot to dock to outside of Earth’s gravity well. This latter point is becoming ever more pertinent now that the goal is to have refueling stations in orbit around Earth as part of NASA’s new Moon landing program.

What the ISS also demonstrates – tragically – is that expensive space exploration programs tend to be heavily linked into politics, and by extension military objectives. With the scientific progress of the Cold War era being overshadowed by the looming threat of planetary-scale annihilation, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty sought to prohibit space-based weapons of mass destruction, as well as regulate access to space as being essentially a public good.

It was against this background that the Soviet Union began its Salyut program in 1971. This program sought to develop ostensibly only space stations that were intended solely for civilian and scientific use, but ended up being a dual-use project.

Manned Satellite Or Space Station

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the military Salyut stations was that they showed of how little use such military stations are. Although the Almaz (Russian: ‘Алмаз’, or ‘Diamond’) Orbital Piloted Station (OPS) space stations were intended to be surveillance platforms, their performance was abysmal. Three stations (Salyut 2, 3 and 5) were put into orbit, of which Salyut 2 (OPS-1) got shredded by debris from the Proton rocket’s third stage when it exploded.

Salyut 3 (OPS-2) was marginally more successful, with its onboard cameras performing their surveillance duties and the Rikhter R-23 autocannon being to this day the only cannon to have been fired in space. Only one of the three crews that tried to dock with the station managed to do so successfully. The idea behind this station was that the crew could develop the film from the cameras, scanning in important images for transmission to Earth, while other images would be dropped back to Earth in a return capsule. And as we mentioned, the autocannon was fired at least once, but only while the station was uncrewed.

The last OPS Salyut station was Salyut 5 (OPS-3), launched in 1976. It was visited by two Soyuz crews before the station ran out of propellant and was deorbited shortly after the failed third docking attempt. This station was more or less dual-use. Although its primary purpose was of a military nature, the crew also performed scientific experiments. Its successor in the form of OPS-4 would never be launched, however, as the crewed Almaz program was cancelled in favor of the uncrewed Almaz-T surveillance satellites and their successors.

Although perhaps in the 1970s having an orbiting film development lab would have made sense, it soon became clear that uncrewed satellites would offer significantly more bang for the buck. This essentially left only the civilian Salyut (ODS) program to continue, with the Salyut 6 and 7 stations.

Ultimate Sacrifice

Despite how routine it may seem to have crewed spacecraft launch into space, dock with a space station and descend, the first Salyut station (DOS-1, for Durable Orbital Station) made it abundantly clear just how brutal and unforgiving each part of this process can be. Launched in 1971 on April the 19th, the mission initially appeared to be trouble-free, with the orbiting station being assigned the designation Salyut 1, to indicate mission success.

However, during the initial docking attempt by the Soyuz 10 crew, their attempts to hard dock with the station failed and they were ultimately forced to abandon their attempt. The crew managed to return safely to Earth, leaving it to the Soyuz 11 mission to attempt the docking again. This was attempted on June 7th, 1971, and hard docking was successful, allowing them to be the first ever crew in a manned space station.

Salyut 1 would be their home for 22 days, during which they performed experiments and dealt with a small fire on day 11. At the end of their mission, they loaded scientific specimens, along with film and other gear into the Soyuz 11 craft and prepared to return to Earth. Although everything seemed to go fine during descent, the ground-based crew assigned to recovery of the Soyuz capsule got no response from the crew. Upon opening the capsule, they found that all three men had died.

Ultimately it was determined that during the separation of the descent and service module prior to reentry, a pressure equalization valve had been jolted loose by the explosive bolts, which had allowed the landing module to depressurize. Although there were signs that the crew had attempted to close the valve, it was not in a location where it was easily accessible, and they met a gruesome demise through asphyxiation as their craft hurtled back towards the safety of Earth.

The Next Generation

With each success and failure within the first generation of Salyut stations, both OPS and DOS, harsh lessons were learned. The Soviet engineers had opted for an automated docking system from the beginning, but failed docking attempts kept occurring, which forced them to refine the docking procedures and systems. Failed station launches led to revisions and improvements. The tragic accident with Soyuz 11 resulted in the original three-man crew configuration in Soyuz capsules being reduced to two, so that both could wear a Sokol space suit which would keep them safe in case of sudden decompression or other hazardous events.

While the first civilian Salyut DOS stations (DOS-1 and DOS-4, or Salyut 1 and 4) were essentially like the Almaz stations, the second generation were significantly larger and more advanced. Rather than a single docking port, they featured two of these, allowing for resupply missions that allowed crews to stay onboard for months. The first second-generation station, Salyut 6 would remain in orbit for five years, with no noticeable incidents.

Less fortunate was Salyut 7 (DOS-6), which suffered major electrical and communication issues while it was uncrewed in orbit. This led to the heroic rescue mission by the Soyuz T-13 crew, who managed to not only perform a manual docking with the unresponsive station, but also repair it to the point where it remained in use for years.

Intended as the transition test bed from the existing monolithic space stations, Salyut 7 pioneered modular station concepts that would be used in its successor, DOS-7, as well as adding a focus on creature comforts since crews would be living in space for months on end. Rather than being branded Salyut 8, DOS-7 would form the core of a new, modular station called Mir and be the first of its kind while still carrying the Salyut legacy. Launched in 1986, Mir survived the collapse of the Soviet Union, and heralded the beginning of international cooperation in space.

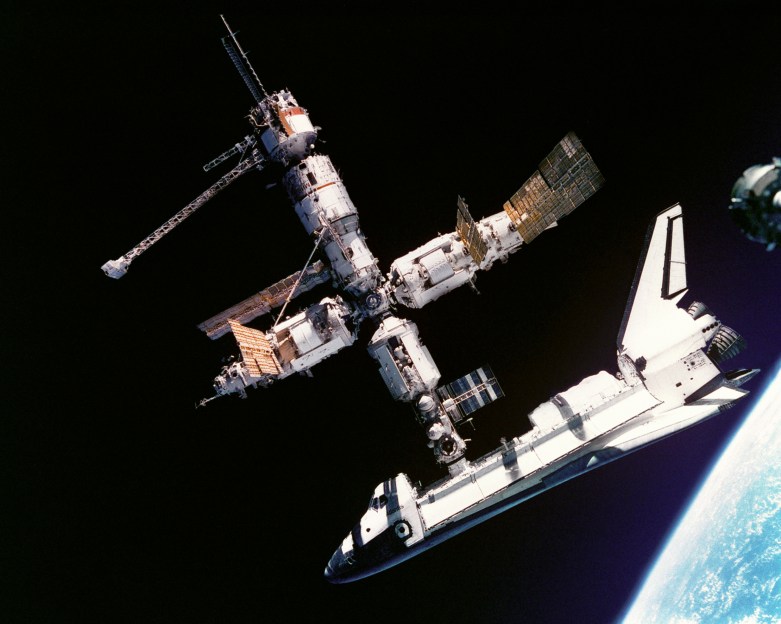

Skylab, which reused a lot of hardware from the Apollo Moon program, was the US’s only solo space station in the 1970s, but the US Space Shuttle would end up docking with Mir repeatedly over the course of years as part of the Shuttle-Mir program. As part of a discussion between the US and Russia during the 1990s, it was decided that the follow-up program to Mir would not be Mir-2, but instead the International Space Station.

The Russian elements of the ISS are firmly based in the Salyut legacy, with Zvezda (DOS-8) forming a core module of the space station. The Russian modules were launched and docked in an automated fashion, while the other modules were delivered by the Space Shuttle and assembled essentially by hand, ultimately resulting in the ISS we know today. It is this station which provides us with a glimpse not only of the long history of the Salyut program and its many sacrifices, but also of the future of humanity in space.

When the ISS will be deorbited at some point in 2031, the major question remains what will take its place, as humankind continues to try and figure out what space means to it. Both crew members on the ISS as well as those who ventured away from Earth during the Apollo missions have remarked on the impact of seeing Earth from further away, and to gaze into the depths of the Universe far beyond the reaches of Earth’s atmosphere.

Maybe the most essential aspect of these space missions is that it teaches us that to truly understand the Earth and ourselves, we first have to get away from both for a while.

(Header image: the Space Shuttle Atlantis connected to Russia’s Mir Space Station, as photographed by the Mir-19 crew on July 4, 1995. Credit: NASA)

The Soviet Space Station Program: From Military Satellites to the ISS

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments