Among the daily churn of ‘Web 3.0’, blockchains and cryptocurrency messaging, there is generally very little that feels genuinely interesting or unique enough to pay attention to. The same was true for OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s Ethereum blockchain-based Worldcoin when it was launched in 2021 while promising many of the same things as Bitcoin and others have for years. However, with the recent introduction of the World ID protocol by Tools for Humanity (TfH) – the company founded for Worldcoin by Mr. Altman – suddenly the interest of the general public was piqued.

Defined by TfH as a ‘privacy-first decentralized identity protocol’ World ID is supposed to be the end-all, be-all of authentication protocols. Part of it is an ominous-looking orb contraption that performs iris scans to enroll new participants. Not only do participants get ‘free’ Worldcoins if they sign up for a World ID enrollment this way, TfH also promises that this authentication protocol can uniquely identify any person without requiring them to submit any personal data, only requiring a scan of your irises.

Essentially, this would make World ID a unique ID for every person alive today and in the future, providing much more security while preventing identity theft. This naturally raises many questions about the feasibility of using iris recognition, as well as the potential for abuse and the impact of ocular surgery and diseases. Basically, can you reduce proof of personhood to an individual’s eyes, and should you?

Observe The Happy Fun Orb

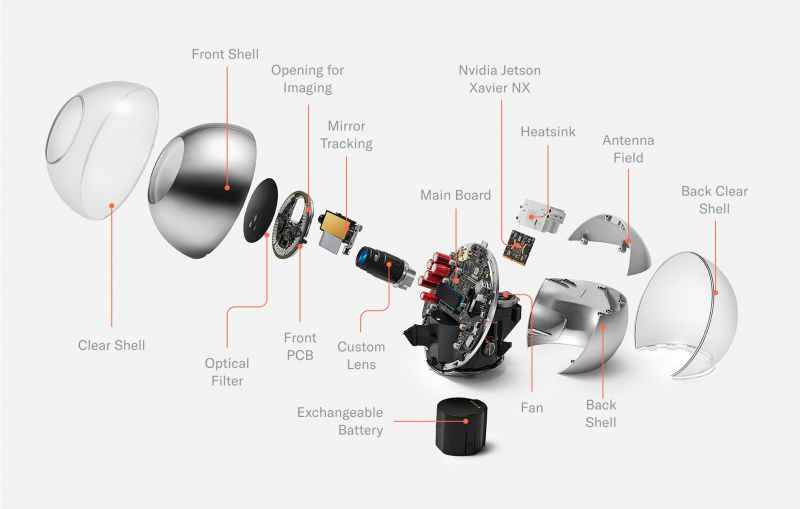

Although one may question initially the size and heft of the World ID Orb, there is quite a bit of hardware packed into it, for good reason as we’ll see in a moment. A teardown of the device shows the optics and PCBs. Most of the processing capacity is provided by an Nvidia Jetson Xavier NX system-on-module (SoM), with power for the entire system provided by a nearly 100 Wh, swappable battery pack, composed of 8 single 18650 Li-ion cells.

This is enough to use the Orb in a portable fashion without having to stay near a power source. The rest of the device’s heft comes from the big telephoto lens and mirror system including gimbal system. This allows for a hapless volunteer’s eyes to be captured without requiring them to press their eyes right up to the sensor.

This optical system reveals a commonality among iris scanners, in that they generally do not use the visual spectrum, but rather multi-spectral, near-infrared radiation to discern as many details in the iris as possible. The front PCB of the Orb reveals the final sensors, including a thermal camera. Much of this seems to be related to the anti-tampering measures mentioned by the available documentation, as well as ensuring that a live person is in front of the sensors.

Most of this hardware is open source, with on the Worldcoin GitHub account. However, this does not include the anti-tamper systems, and requires the use of Autodesk’s Eagle software to use the project files. Creating your own Orb is thus only partially possible, but allows for some insights into the design behind it. Incidentally, although each Orb is Internet-connected, the iris scans are said to not be sent to the World ID servers, but rather stay on the Orb.

Here the iris scans are processed into an ‘iris code’ which is supposed to uniquely identify the irises of the individual, without being reversible. Whether or not this is the case is a question which security researchers have no doubt already thrown themselves at with sheer abandon. This is of course not the question which we seek to answer here, which is whether a person’s eyes – or rather their retinas – can be directly correlated with personhood.

Measure Of A Person

Despite TfH equating each unique human being with a ‘person’ as well as personhood with its Proof of Personhood take, it shouldn’t take more than a casual glance to realize that the definition of ‘personhood‘ is at best a contentious one, even without the discussion on non-human personhood. What is perhaps commendable here is that TfH attempts to be as inclusive as possible, which is how they arrived at the conclusion that a person (as in a human being) is most uniquely defined (for now) through biometrics, of which the iris is the most unique because of the high level of entropy in its structure.

At face value this is technically correct, as without more invasive scanning techniques, the iris has the advantages of being quite static in its structure, while also being well-protected unlike fingerprints, while still being easy to scan. Yet, iris recognition has similar flaws as other types of biometrics in that they can be fairly easily faked, with the Chaos Computer Club in 2017 demonstrating the circumventing of the iris recognition feature in the Samsung Galaxy S8 with a photograph of the eye plus a contact lens to get the curvature.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) touches upon many of the issues with iris recognition, with the acknowledgement that iris recognition can be used for surveillance as well with much better results than facial recognition. Similarly, high-resolution images of irises are easy to get merely by photographing the victim with a suitable camera, which makes faking these biometrics quite easy. In the end, widespread iris-based biometrics will invite increasingly more sophisticated attempts to both fool scanners and to prevent said fooling.

If copying and wearing someone’s irises makes you effectively into that person for the system, it would seem to be a spurious correlation at best.

No Iris No Service

Beyond the majority of humans who are living their lives with two unmodified, healthy Mk-1 eyeballs, there are many individuals who either have opted to abandon their original irises for cosmetic reasons, or who suffered a genetic, traumatic or medical condition leading to partial or complete loss of the iris or its functions, regardless of whether this affects the rest of the eye as well. Even something as routine as cataract surgery can affect an iris, as detailed by Ishan Nigam et al. (2019) in a cohort study among cataract surgery patients which found a significant drop in iris scan matches, much as had been found in 2004 already by Roberto Roizenblatt and colleagues.

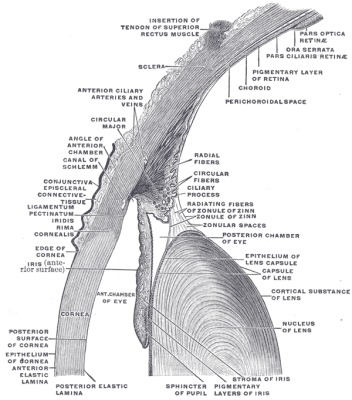

Although the iris is a quite static structure – generally speaking – it is important to understand that it is not a solid structure, but rather it consists of intricate structures which provide diaphragm-like functionality for the eye, as well as aperture control via embedded muscles (the iris sphincter and dilator muscles). In total, the iris itself consists of six layers, from front to back:

- anterior limiting layer

- stroma

- sphincter muscle

- dilator muscle

- anterior pigment epithelium

- posterior pigment epithelium

Most of what we can see directly of the iris when observing the eye is the stroma of iris. This is a fibrovascular layer, which as the name suggests consists of fibrous tissue interlaced with blood vessels, as well as nerves. It is this lacework of fibers that in a sense forms the unique pattern much like a person’s fingerprints. The color of the iris is the result of an intricate optical interaction between the (dark) pigmentation in the stroma as well as the epithelium, in addition to their textures, fibrous structures and blood vessels. It is this complex structure of interlaced structures which make that the iris has such a high level of entropy, and also why the amount of pupil dilation affects the result of an iris scan.

As alluded to earlier, however, there are many conditions which affect the iris, with some of them summarized by the American Academy of Ophthalmologists. Of these, inflammation of the uvea (uveitis) of which the iris is also a component is a common condition that can severely damage the eye, including the iris (iritis). One of the most common causes of uveitis that affects the iris is the herpes simplex virus (HSV, causing Herpes Simplex Uveitis), usually during reoccurrences of HSV.

For those who have congenital, traumatic or other types of damage to the iris, the use of prosthetic iris devices (Artificial Iris, or AI) are an option. Such an AI covers part of the functionality of a natural iris, enabling something approaching normal vision, but naturally rendering them impervious to iris recognition, as an AI is very different from the biological version. These AIs are often the only option after botched cosmetic iris surgery (warning, graphical content) as well, which would preclude the use of iris recognition whether said cosmetic iris surgery is successful or not.

Squishy Brains

As much as we’d like to use biometrics like a fingerprint, iris- or retinal scan as an absolute part of who we are, the fact of the matter remains that the only part of our bodies which is intrinsically tied to us as an individual is our brain. Swap some brains about between bodies, and you’d still be ‘you’, just slightly confused while you figure out the details of a new body. This is perhaps the fundamental flaw with biometrics: until we can directly scan brain structures (non-fatally, natch), every other form of biometrics will at most be an approximation of what true biometric authentication would entail.

Even our brains can and will change over time due to neuroplasticity, diseases, trauma, etc. Despite this, our overarching sense of ‘self’ and the memories which we carry with us, are firmly encoded in the squishy tissues of this amazing organ, thus forming our unique personalities, shaping our dreams and desires, and making us into the person we are today. Yet until the day comes that someone presents an Orb that can literally scan human brains, scanning irises is a passable, imperfect, approximation.

The World ID Orb and the Question of What Defines a Person

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments