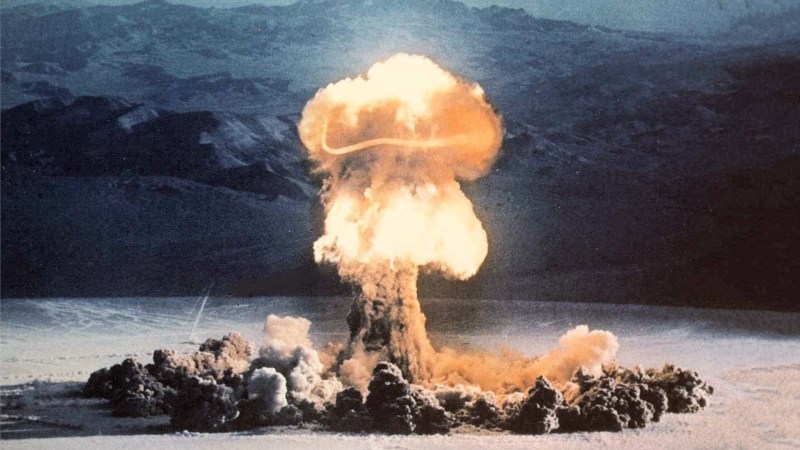

Before the first atomic bomb was detonated, there were some fears that a fission bomb could “ignite the atmosphere.” Yes, if you’ve just watched Oppenheimer, read about the Manhattan Project, or looked into atomic weapons at all, you’ll be familiar with the concept. Physicists determined the risk was “near zero,” proceeded ahead with the Trinity test, and the world lived to see another day.

You might be wondering what this all means. How could the very air around us be set aflame, and how did physicists figure out it wasn’t a problem? Let’s explore the common misunderstandings around this concept, and the physical reactions at play.

Not Fire, But Fusion

The main misconception is that a fission bomb could “ignite” the atmosphere in the sense that the air itself would burn. It comes down to terminology; the word “ignite” is most familiarly used to refer to fire. Combustion is a chemical reaction, involving the breaking of molecular bonds between atoms. This results in a release of energy in the form of heat, light, and so on. However, the species typically present in our atmosphere are, by and large, not very flammable. The nitrogen that makes up the greatest proportion of air certainly doesn’t want to burn; neither does argon or carbon dioxide, for that matter. If they readily reacted in such a way with the oxygen in the air, we’d already know about it.

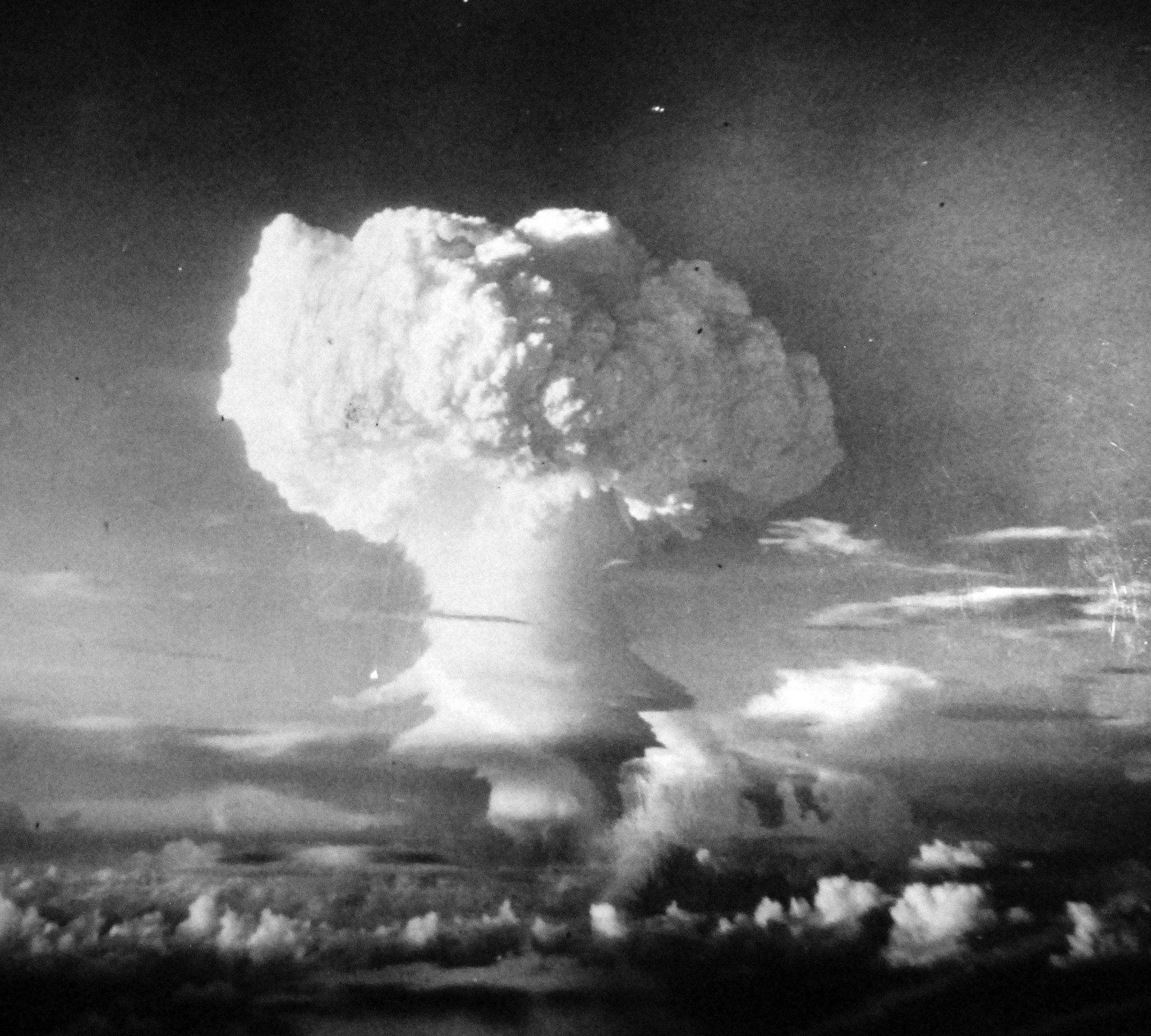

Instead, the concern was that the great energy output from a fission bomb could instead “ignite” a nuclear chain reaction in the atmosphere. The possibility was considered as early as 1942, several years before the successful Trinity test. Physicist Edward Teller raised the idea that the intense heat created by a fission bomb could cause hydrogen atoms in the air and water to fuse together into helium. The idea was that this could then release more energy in a runaway chain reaction that quickly consumed the entire atmosphere, functionally destroying the Earth as we know it. Concerns that a reaction could occur in the world’s oceans were also raised along the way.

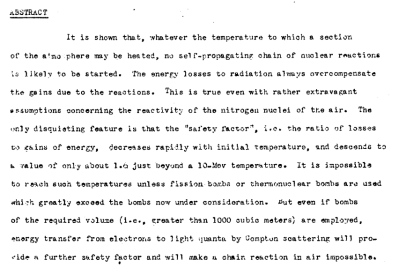

The matter was studied, with Teller working with Emil Konopinski on the problem. The two published their findings in a report some six months before the Trinity test took place. The two concluded that no matter how hot any one section of the Earth’s atmosphere might become, a runaway nuclear chain reaction was likely to be sustained. This was due to the fact that even if any fusion reactions did occur in the open atmosphere, the energy lost to the surroundings via radiation was far in excess of the extra energy released. Thus, no self-sustaining chain reaction would occur.

The report examined a variety of potential reactions, including those concerning the potential for nitrogen to get involved, but concluded there was no risk of a chain reaction occurring. Even in the event of the detonation of a truly massive thermonuclear bomb of over 1000 cubic meters in size, energy transfers from Compton scattering would shed enough energy to prevent a runaway self-sustaining nuclear reaction in air. The numbers indicated there was a large safety factor by virtue of the unsustainability of chain reactions in the atmosphere.

The matter was largely considered closed, but resurfaced in the 1970s. This was largely due to an essay published in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists rehashing the concerns around nuclear ignition of the atmosphere during the Manhattan Project. Physicist Hans Bethe would go on to rebut the issue once more, noting that nuclear fusion reactions are only sustained under great pressure, something not present in the atmosphere or the Earth’s oceans.

Fundamentally, nuclear weapons proved to be incapable of destroying the world in a single detonation. They remain capable of doing great harm, regardless, and questions still rage as to whether they could be the end of civilization by other mechanisms, such as nuclear winter. In any case, past decades have seen the world grow far more wary of their use, and we yet hope that such events may never again come to pass.

Why Nuclear Bombs Can’t Set The World On Fire

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments