Since the very early 1990s, we have become used to ubiquitous digital mobile phone coverage for both voice and data. Such has been their success that they have for many users entirely supplanted the landline phone, and increasingly their voice functionality has become secondary to their provision of an always-on internet connection. With the 5G connections that are now the pinnacle of mobile connectivity we’re on the fourth generation of digital networks, with the earlier so-called “1G” networks using an analogue connection being the first. As consumers have over time migrated to the newer and faster mobile network standards then, the usage of the older versions has reduced to the point at which carriers are starting to turn them off. Those 2G networks from the 1990s and the 2000s-era 3G networks which supplanted them are now expensive to maintain, consuming energy and RF spectrum as they do, while generating precious little customer revenue.

Tech From When Any Phone That Wasn’t A Brick Was Cool

All this sounds like a natural progression of technology which might raise few concerns, in the same way that nobody really noticed the final demise of the old analogue systems. There should be little fuss at the 2G and 3G turn-off. But the success of these networks seems to in this case be their undoing, as despite their shutdown being on the cards now for years, there remain many devices still using them.

There can’t be many consumers still using an early-2000s Motorola Flip as their daily driver, but the proliferation of remotely connected IoT devices means that there are still many millions of 2G and 3G modems using those networks. This presents a major problem for network operators, utilities, and other industrial customers, and raises one or two questions here at Hackaday which we’re wondering whether our readers could shed some light on. Who is still using, or trying to use, 2G and 3G networks, why do they have to be turned off in the first place, and what if any alternatives are there when no 4G or 5G coverage is available?

How Big Is The Problem And Where Can We Go From Here?

The first question finds its answer fairly easily, before we’ve even considered IoT devices. Take a journey away from the cities and main transport arteries, and it’s likely you won’t have to go far before the faster connections stop and 2G is your only option.

Data rates drop to levels from the dial-up age with GPRS and EDGE, and any electronic devices you own with a speaker start that characteristic 2G chirping as they pick up stray RF from your phone. Speaking from a European perspective this happens even in places one might consider well populated, for example when a Eurostar train travels through the Belgian countryside.

Aside from the convenience of rural mobile phone users, there are plenty more places where older tech can be found. In the estimated 7 million British smart meters which will go offline after the turnoff for example, or in the numerous anecdotes of cars with online systems behaving strangely when they lose their cellular connection. But beyond that we have several decades of devices of all kinds that use a cellular connection, while many will like those smart meters be owned by utilities or public bodies, countless more will be in private hands. When the cell service they rely on stops it’s likely many owners will only become aware when the device they rely on ceases to work. A quick online search finds plenty of inexpensive devices still on sale with 2G connectivity, so it’s not even a legacy issue.

So if the older networks are still required in some form, just why are they being turned off? Here the argument is mostly economic, despite those rural travelers and IoT devices, it’s no longer economic for the carriers. The older technologies still occupy a significant quantity of valuable spectrum, and the infrastructure running them is power-hungry for little revenue. A remote sensor with a 2G SIM in it uses a tiny quantity of data, nowhere near enough to pay for the network it uses.

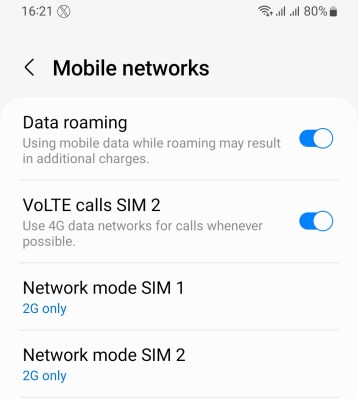

As to alternatives, the easy answer is that every device should simply upgrade to 4G or 5G, though we expect the scale of the task would make that impossible in anything but a very long timescale, and even then the costs could be difficult to bear. Can it be kept then?

At the network end we have a question for any readers who work in the industry, if the 2G network is vital but has such limited use, is it possible to maintain a 2G network shared by carriers on a very small piece of shared spectrum? We know that a 2G implementation using SDR technology is a fraction of the size and power consumption of the large cabinet-sized base stations which went in when GSM was a new technology, could such a network of low-bandwidth 2G cells provide just enough to keep all those smart meters and other devices working?

Can You Take A Little Bit Of The Network With You?

This neatly brings us to the measures a Hackaday reader might be able to take themselves. A femtocell is a very small scale mobile phone cell sometimes used by networks to fill in small gaps in coverage, but it is also something that can be found in a domestic setting both as a commercial product and from a hacker perspective. The commercial home femtocells are largely obsolete because most phones now offer Wi-Fi calling, but they usually take the form of a box similar to a home router that would create a short-range cell using the home broadband connection as a backhaul. During the 3G era they were sold by carriers as a home upgrade, but at least where this is being written the service has largely been switched off. It’s possible that these technologies could return to be used in some situations, but they would require carrier buy-in.

All isn’t lost for the more adventurous souls though, because 2G networks have for quite some years been an open book in terms of the way they work. With a relatively inexpensive SDR and open source software such as Osmocom or OpenBTS it’s possible to host your own 2G cellular network giving internet connectivity back to your devices with no carrier involved. We feel duty bound at this point to remind you that most countries take a dim view of unlicensed spectrum usage.

From reading up on the tale of 2G and 3G switch-off in both the countries that have done it, and those that intend to do it, the overall impression is of a seamless operation for the majority of people who long ago switched to 4G or 5G without noticing, but something of a headache for rural users and owners of 2G-connected IoT devices. It appears that 2G in particular is one of those technologies which gained so much traction that we seem doomed never to be rid of it.

Header image: Luis, CC BY-SA 4.0.

2G Or Not 2G, That Is The Question

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments