Perhaps no words fill me with more dread than, “I hear there’s something going around.” In my experience, you hear this when some nasty bug has worked its way into the community and people start getting whatever it is. I’m always on my guard when I hear about something like this, especially when it’s something really unpleasant like norovirus. Forewarned is forearmed, after all.

Since I work from home and rarely get out, one of the principal ways I keep apprised of what’s going on with public health in my community is by listening to my scanner radio. I have the local fire rescue frequencies programmed in, and if “there’s something going around,” I usually find out about it there first; after a half-dozen or so calls for people complaining of nausea and vomiting, you get the idea it’s best to hunker down for a while.

I manage to stay reasonably well-informed in this way, but it’s not like I can listen to my scanner every minute of the day. That’s why I was really excited when my friend Mark Hughes started a project he called Boondock Echo, which aims to change the two-way radio communications user experience by enabling internet-backed recording and playback. It sounded like the perfect system for me — something that would let my scanner work for me, instead of the other way around. And so when Mark asked me to participate in the beta test, I jumped at the chance.

Hardware Design

If Boondock Echo sounds familiar, it’s probably because we’ve written about it a few times already. The project was entered in the 2022 Hackaday Prize, and actually ended up winning the 4th place award that year. There’s also a Hackaday.io project, and as a personal point of pride, Mark and Kaushlesh Chandel, now the firmware architect on the project, started their collaboration after meeting at a Hack Chat back in 2021. We get results!

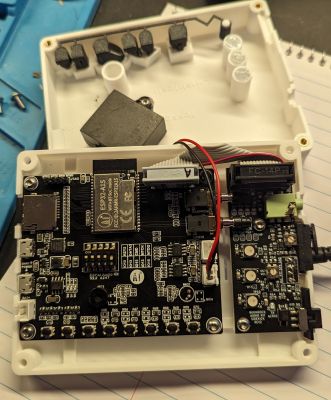

The Boondock Echo beta test units I have are based on an AI-Thinker ESP32 Audio Kit, a commercially available dev board that’s specialized for digital audio applications. It wasn’t the team’s first choice for a platform, not by a long shot, and the path to it is an object lesson in the often harsh realities of product design. The original design called for the same audio module as the full AI-Thinker dev board, the ESP32-A1S. They designed a nice PCB around it with all the interface electronics needed to support a Baofeng handy talkie along with a good-quality speaker, and ordered up a bunch of the ESP modules.

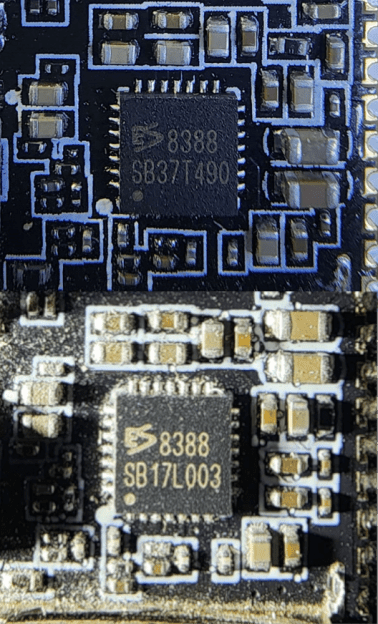

However, they found that despite identical part numbers, FCC ID numbers, and external arrangements, not all the modules they had ordered for the first run worked as planned. It was only when they took the RF shielding off the modules that they discovered the reason: significant differences in board layout and components used, particularly in the area of the ES8388 audio codec.

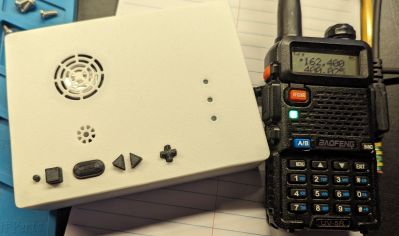

From the sound of it, sorting all this out was a huge time-sink for the team. With no way to tell from the outside whether a module would work in their design, they eventually had to cut their losses and go with the pre-built Audio Kit board with a small, custom-built “sidekick” board that connects to the Baofeng. It’s a sensible approach, especially given the circumstances, and not only does it allow them to actually ship working units, but it also gives them a chance to move to another, more capable platform later.

They Don’t Call It “Easyware”

From the outset, let me make it clear that I suspect I’ve been anything but the typical beta tester, at least from the team’s point of view. Boondock Echo was designed primarily to retransmit the audio it receives; it’s right in the name, after all. Mark’s original vision for Boondock Echo was based on his experience with California wildfires and the spotty radio communications that often interrupted the timely flow of news and evacuation orders But my immediate interest in Boondock Echo is for recording public safety radio calls from my scanner. So, rather than just plugging into the Baofeng handy talkie they sent along with my test unit, I had to go rogue and try my own thing. Sometimes you just have to break things.

And break things I did. Try as we might, the first Boondock Echo I got just wouldn’t work. We tried everything — punching holes in my firewall, disabling my Pi-Hole ad blocker, and even setting up a hotspot on my phone to bypass my home WiFi. That last attempt actually worked, meaning that the was something specific about my network that was making it impossible for the device to register with the Boondock Echo server. This resulted in some very long conference calls with Mark, KC, and hardware architect Jesse Robinson, and kudos to them for trying everything to get me online. But they simply had to go back to the drawing board.

Things went much better on the second attempt. They sent me a new unit with updated firmware running on essentially the same hardware, with an updated and much-improved enclosure. I was able to get this device online with very little effort; all that was required was editing a config file on the included SD card with my WiFi credentials and rebooting. However, audio from my scanner — a Bearcat BCD996P2 — was not being recorded. Again, the team was very professional about it, getting on a conference call with me and later continuing the discussion over a Discord chat. We eventually figured out that the line-out jack on my scanner just wasn’t putting out as much signal as the Baofeng external speaker jack does. KC went off and changed the firmware to increase the dynamic range of the audio input, and between that change and a little bit of adjustment of the attenuator on the side-kick board, I was finally recording audio.

My Experience

At least in my case, once the Boondock Echo is online, there’s not much need to interact with it. That doesn’t mean you can’t, of course — there are buttons on the front panel that let you control the volume of the internal speaker, scroll back and forth between recorded sound clips, and even a push-to-talk button that will record a clip through the front panel mic for transmission on the Baofeng, if you’re suitably licensed to do so. There are also some LEDs that tell you the current status of the device. All these are thoughtful features, but in practice, I found that all the real action is in the Boondock Echo web interface.

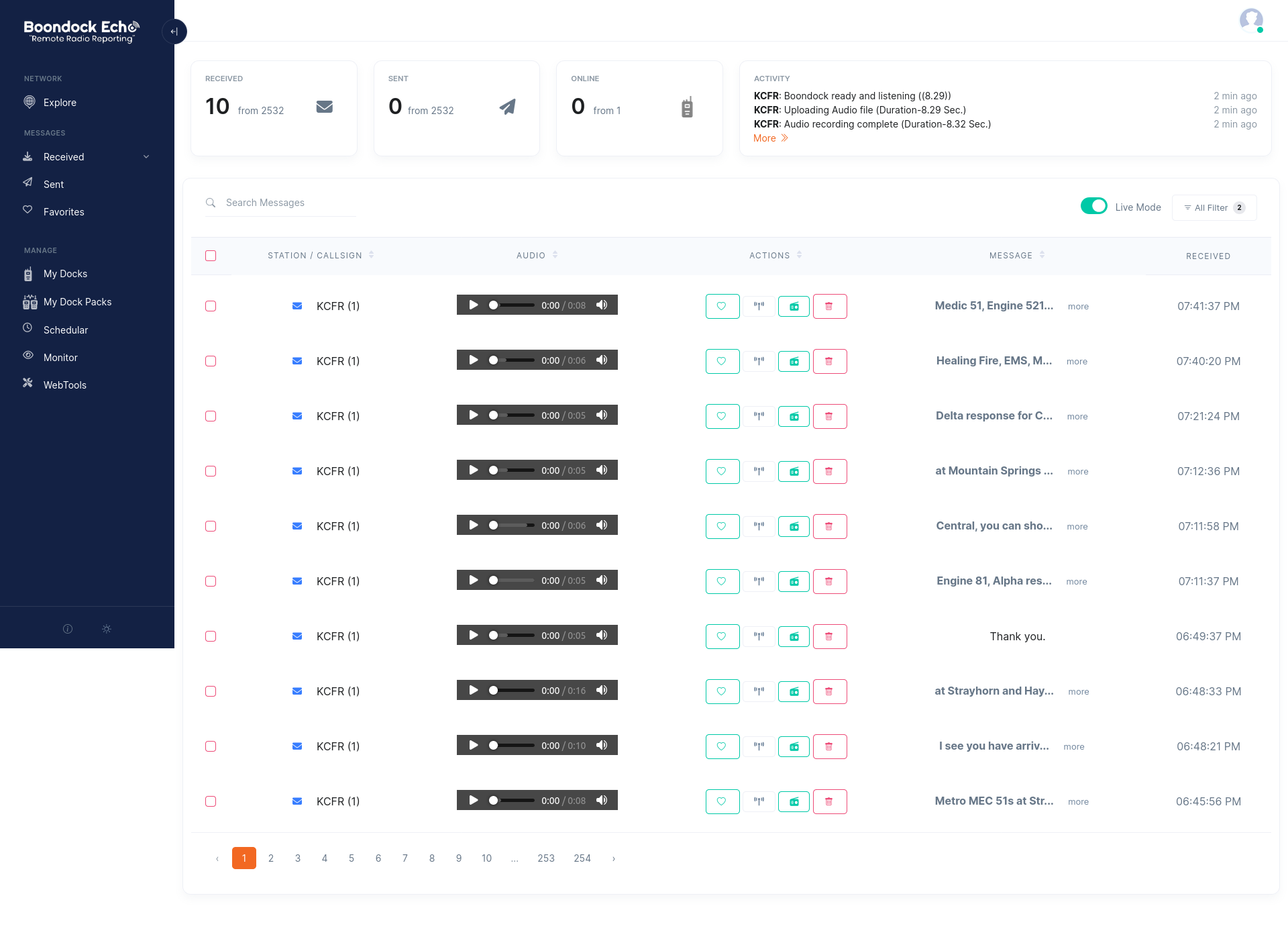

To be clear, the Boondock Echo application isn’t running on the ESP32 built into the device. Rather, it’s hosted on AWS, for security and scalability in the future. The ESP32 in the device takes care of all the local functions, like digitizing the audio, running the local interface, and playing back audio clips locally. I find the design of the web app pretty good; it’s functional without a lot of flash or fluff, but still good-looking and intuitive. The main page has a list of audio clips that have been recorded by your device — or devices; the idea of a “dock pack” of multiple Boondock Echo devices is supported, for capturing audio from multiple sources. Each entry has an embedded player to let you listen to the clip on your PC or phone, along with buttons that send the clip back to the Boondock Echo device for playback over the internal speaker, or for retransmission over the attached transceiver. Again, a proper license is required to transmit.

One of the neatest features of Boondock Echo, and the one that I was most interested in testing, is online transcription of recorded clips. Clips are sent to OpenAI’s Whisper API for transcription, and all things considered, the results are pretty good. There are obviously limits, of course; it doesn’t seem like Whisper’s training model includes such catchy phrases as “patient contact green,” which is used around here when an arriving unit encounters a patient who isn’t in any immediate danger. Transcription of specialist speech like this is spotty, with results like “face your contact green,” or “Trojan 41” for “Engine 41.” I’ve also noticed that when in doubt, Whisper seems to skew toward the very polite, and even a bit amorous; there are plenty of “Thank very much” and “Have a great day” transcripts, which I’m reasonably sure isn’t what was said, and the occasional “I love you” sprinkled in, especially on channels where users tend to talk way too loud.

That brings up a good point, and one that there’s probably not much the Boondock Echo team can do much about right now. The quality of audio in public service radio can be all over the place, ranging from barely audible to over-driven and distorted. Certain dispatchers are soft-spoken, others louder and more confident on the air, while firefighters and paramedics often get into situations where they can’t help but get a bit excited. There are also what I call “incidental radio operators,” such as the nurses who talk to paramedic units in the field and take reports on the radio. These people are medical professionals without much radio training, and they all tend to “swallow the mic,” resulting in severe distortion.

The team hopes to implement some DSP algorithms to clean up audio before it goes off to Whisper, but that may have to wait until they make some hardware changes to the Boondock Echo. That’ll be a huge benefit to one of its most useful features: keyword monitoring. Users can set up monitors that scan transcripts for specific keywords and then perform an action. In my case, I have monitors set up for the names of roads my family and friends live on; if there’s an ambulance or fire call for my parents’ address, I want to know about it instantly. At this time, notification when a keyword matches is limited to an email, but future actions will include SMS texts and even IFTTT, so you can do pretty much anything you can imagine. It all depends on the accuracy of the transcription, though, since the match with the keyword needs to be exact. It might be a good idea to implement the Soundex algorithm here, or at least make it an option.

Hiccups aside, I’ve been very pleased with how my Boondock Echo has performed, especially considering that it wasn’t built to support my specific use cases. I’m still very early in the process of integrating it into my workflow, but I can see a lot of potential uses for it. I can imagine using this as the basis of a local information network, for people who don’t want to sit in front of a scanner all day listening to all the routine stuff, but really want to know when “the big one” hits. I’m also keen to try setting up a “store and forward” simplex repeater for ham radio experiments; a Boondock Echo operating in offline mode would make this simple to set up.

Hats off to the whole Boondock Echo team for going from idea to working project in such a short time, and thanks for inviting me along for the ride. I’m looking forward to seeing where it goes next.

Hands on with Boondock Echo

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments