Since China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) unveiled its KUN-24AP containership at the Marintec China Expo in Shanghai in early December of 2023, the internet has been abuzz about it. Not just because it’s the world’s largest container ship at a massive 24,000 TEU, but primarily because of the power source that will power this behemoth: a molten salt reactor of Chinese design that is said to use a thorium fuel cycle. Not only would this provide the immense amount of electrical power needed to propel the ship, it would eliminate harmful emissions and allow the ship to travel much faster than other containerships.

Meanwhile the Norwegian classification society, DNV, has already issued an approval-in-principle to CSSC Jiangnan Shipbuilding shipyard, which would be a clear sign that we may see the first of this kind of ship being launched. Although the shipping industry is currently struggling with falling demand and too many conventionally-powered ships that it had built when demand surged in 2020, this kind of new container ship might be just the game changer it needs to meet today’s economic reality.

That said, although a lot about the KUN-24AP is not public information, we can glean some information about the molten salt reactor design that will be used, along with how this fits into the whole picture of nuclear marine propulsion.

Not New, Yet Different

The idea of nuclear marine propulsion was pretty much coined the moment nuclear reactors were conceived and built. Over the past decades, quite a few have been constructed, with some – like commercial shipping and passenger ships – being met with little success. Meanwhile, nuclear propulsion is literally the only way that a world power can project military might, as diesel-electric submarines and conventionally powered aircraft carriers lack the range and scale to be of much use.

The primary reason for this is the immense energy density of nuclear fuel, that depending on the reactor configuration can allow the vessel to forego refueling for years, decades, or even its entire service life. For US nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, the refueling is part of its mid-life (~20 years) shipyard period, where the entire reactor module is lifted out through a hole cut in the decks before a fresh module is put in. Because of this abundance of power there never is a need to ‘save fuel’, leaving the vessel free to ‘gun it’ in so far as the rest of the ship’s structures can take the strain.

Theoretically the same advantages could be applied to civilian merchant vessels like tankers, cargo and container ships. But today, only the Soviet-era Sevmorput is still in active duty as part of Rosatom’s Atomflot that also includes nuclear powered icebreakers. After having been launched in 1986, Sevmorput is currently scheduled to be decommissioned in 2024, after a lengthy career that is perhaps ironically mostly characterized by the fact that very few people today are even aware of its existence, despite making regular trips between various Russian harbors, including those on the Baltic Sea.

The KLT-40 nuclear reactor (135 MWth) in the Sevmorput is very similar to the basic reactor design that powers a US aircraft carrier like the USS Nimitz (2 times A4W reactor for 550 MWth). Both are pressurized water reactors (PWRs) not unlike the PWRs that make up most of the world’s commercial nuclear power stations, differing mostly in how enriched their uranium fuel is, as this determines the refueling cycle.

Here the KUN-24AP container ship would be a massive departure with its molten salt reactor. Despite this seemingly odd choice, there are a number of reasons for this, including the inherent safety of an MSR, the ability to refuel continuously without shutting down the reactor, and a high burn-up rate, which means very little waste to be filtered out of the molten salt fuel. The roots for the ship’s reactor would appear to be found in China’s TMSR-LF program, with the TMSR-LF1 reactor having received its operating permit earlier in 2023. This is a fast neutron breeder, meaning that it can breed U-233 from thorium (Th-232) via neutron capture, allowing it to primarily run on much cheaper thorium rather than uranium fuel.

The Easy And Hard Parts

Making a very large container ship is not the hard part, as the rapid increase in the number of New Panamax and larger container ships, like the ~24,000 TEU Evergreen A-class demonstrate. The main problem ultimately becomes propelling it through the water with any kind of momentum and control.

Having a direct drive shaft to a propeller requires that you have enough shaft power, which requires a power plant that can provide the necessary torque directly or via a gearbox. Options include using a big generator and electric propulsion, or to use boilers and steam turbines. Yet as great as boilers and steam turbines are for versatility and power, they are expensive to run and maintain, which is why the Evergreen G-series container ships have a 75,570 kW combustion engine, while the Kitty Hawk has 210 MW and the Nimitz has 194 MW of installed power, with the latter having enough steam from its two A4W reactors for 104 MW per pair of propellers, leaving a few hundred MW of electrical power for the ship’s systems.

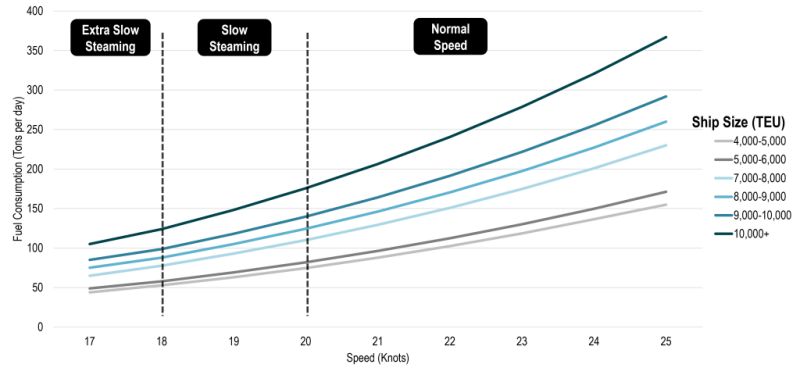

This amount of power across four propellers allow these aircraft carriers to travel at 32 knots, while container ships typically travel between 15 to 25 knots, with the increased fuel usage from fast steaming forming a strong incentive to travel at slower speeds, 18-20 knots, when deadlines allow. Although fuel usage is also a concern for conventionally powered ships like the Kitty Hawk, the nuclear Nimitz has effectively unlimited fuel for 20-25 years and thus it can go anywhere as fast as the rest of the ship and its crew allows.

Got To Go Fast

Today’s shipping industry finds itself as mentioned earlier in a bind, even before recent events that caused both the Panama and Suez canals to be more or less off-limits and forcing cargo ships to fall back to early 19th century shipping routes around Africa and South America. With faster cargo ships traveling at or over 30 knots rather than about 20, the detour around Africa rather than via the Suez Canal could be massively shortened, providing significant more flexibility. If this offering also comes at no fuel cost penalty, you suddenly got the attention of every shipping company in the world, and this is where the KUN-24AP’s unveiling suddenly makes a lot of sense.

Naturally, there is a lot of concern when it comes to anything involving ‘nuclear power’. Yet many decades of nuclear propulsion have shown the biggest risk to be the resistance against nuclear marine propulsion, with a range of commercial vessels (Mutsu, Otto Hahn, Savannah) finding themselves decommissioned or converted to diesel propulsion not due to accidents, but rather due to harbors refusing access on ground of the propulsion, eventually leaving the Sevmorput as the sole survivor of this generation outside of vessels operated by the world’s naval forces. These same naval forces have left a number of sunken nuclear-powered submarines scattered on the ocean floor, incidentally with no ill effects.

Although there are still many details which we don’t know yet about the KUN-24AP and its power plant, the TMSR-LF-derived MSR is likely designed to be highly automated, with the adding of fresh thorium salts and filtering out of gaseous and solid waste products not requiring human intervention or monitoring. Since the usual staffing of container ships already features a number of engineering crew members who keep an eye on the combustion engine and the other systems, this arrangement is likely to be maintained, with an unknown amount of (re)training to work with the new propulsion system required.

With Samsung Heavy Industries, another heavy-shipping giant, already announcing its interest in 2021 for nuclear power plant technology based around a molten salt reactor, the day when container ships quietly float into harbors around the world with no exhaust gases might be sooner than we think, aided by a lot more acceptance from insurance companies and harbor operators than half a century ago.

(Top image: the proposed KUN-24AP container ship, courtesy of CSSC)

China’s Nuclear-Powered Containership: A Fluke Or The Future Of Shipping?

Source: Manila Flash Report

0 Comments